This post is submitted in its entirety by Mariann Beagrie, an MYP Teacher at Beijing City International School, Beijing.

One of the most effective ways to enhance a student’s learning is to give them agency in their learning. In practice, this means using strategies to give them more control over their learning and to ensure that they can see the relevance or meaning of gaining the skills or knowledge they are expected to have.

I previously taught elementary and early childhood students, and giving students agency in their learning has always been a priority of mine. In one school, I initiated a curriculum framework where units of learning were developed in conjunction with the students. Before starting a new unit, we would talk to the students about what they were interested in learning about next. Together, we would brainstorm a list of possible ways we could explore their chosen topic and decide on some of these. Other activities were developed organically as the children learned. Literacy and math objectives were integrated into the learning of the topic. Some of this learning was initiated by teachers in group meetings and small-group activities. Most of it was incorporated into play and activities chosen by the students.

Opportunities to practice skills were placed in areas around the classroom– for example, by placing a train schedule into a train station roleplay area. Other opportunities were introduced by teachers. For example, if the students had decided to make a train, the teacher might pretend to be a ticket collector. Sometimes, the student would choose to write on the tickets – and this would give them the chance to practice their mark-making or writing (depending on what stage they were at). At other times, students might just choose to hand an invisible ticket to the teacher. However, with multiple opportunities like this every day, every student would learn the skills they needed over the course of the year – and they had a lot of agency in how this happened.

Giving students agency was one of my strengths as an elementary and early childhood teacher. However, this year, I started teaching high school students MYP Design and Computer Science and was unsure of what student agency was feasible at this level and with these subjects. Fortunately, the school I am working at decided to offer a year-long professional development opportunity around increasing student agency.

To start with, we learned about 12 different “shifts” (aka changes) that teachers can focus on to increase student agency in their classes. We were asked to rate ourselves on these and then choose 2 to focus on for the year. At this point, I didn’t have a clear picture of exactly what learning in my classroom would look like. So, I rated myself on how I thought things might go based on my current understanding of the curriculum and what I had planned to do. I then picked the two shifts that seemed the most feasible. These were:

- moving from inquiry based on teacher questions, to inquiry based on student questions

- moving from progress monitored by the teacher to progress monitored by the students.

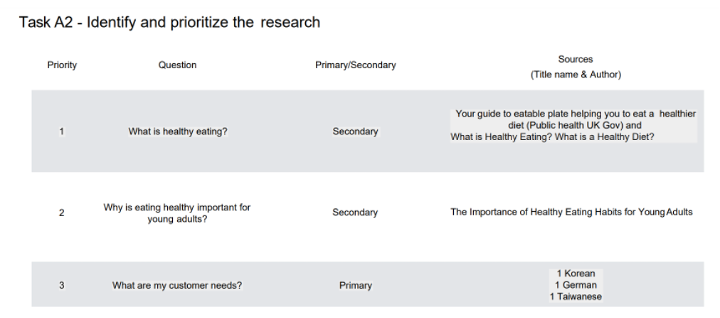

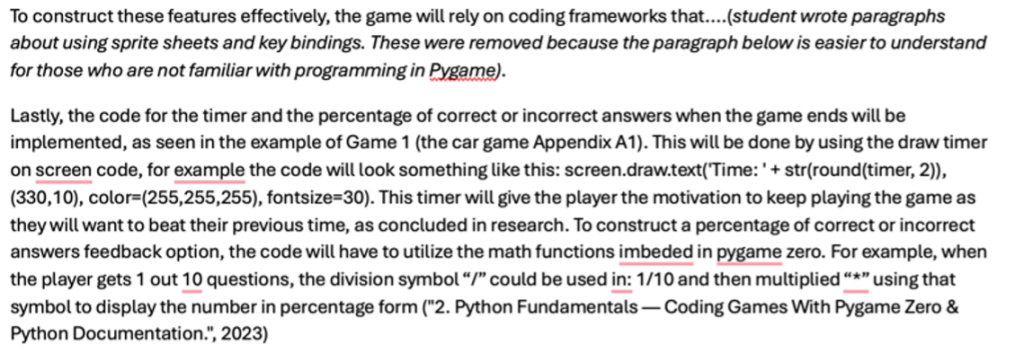

I started by implementing the first shift in the MYP Design units I was teaching. One of the first criteria in the Design Cycle is “constructs a detailed research plan which identifies and prioritizes the primary and secondary research needed to develop a solution to the problem independently”. So, it seemed like this shift would automatically happen in the Design classes. However, I noticed that many of the students were asking questions to meet the assessment criteria but were not using them to guide their inquiry into how to best develop a solution for their target audience.

I think part of the problem was the way that this is criteria is typically assessed. Based on the examples I found, including those on the IB website (below), students generally create research questions that require primary and secondary research. They then indicate the priority and explain how they will research the answer to their question. That’s it. They don’t actually have to do any research to score well on this criteria. On one website that is often shared as a good resource for new MYP teachers, it specifically states “N.B. this is a research plan… not actual research”.

Example of Criteria Aii provided by the IB

I couldn’t see the point of having students come up with a research plan, and not doing any research. So I told my students they needed to actually do the research to find the answer to their questions. However, the first time I taught the unit, many of the students did a very cursory job – they found research so they could get a decent grade, but weren’t invested in learning anything. As a result, students would then run into a lot of difficulty when they started trying to create their solutions.

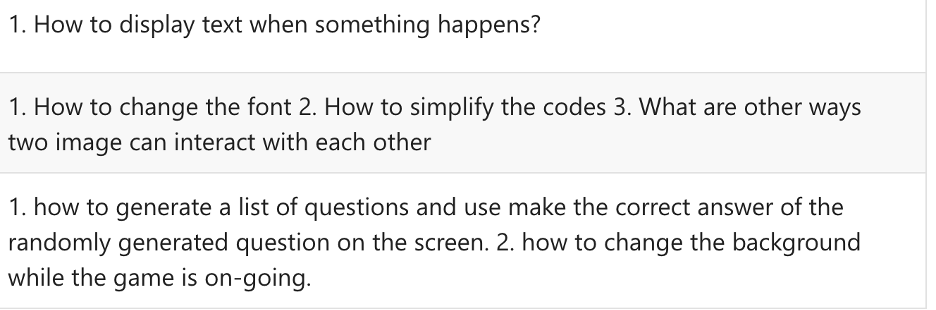

For example, in my Grade 10 unit about creating educational games, many of my students lacked the knowledge they needed to create a game when it was time to do so. I resolved this issue by asking the students to share additional questions they still had after they had tried to make their products.

Some of the questions the students had.

I then designed a few lessons around ensuring the students had the answers to these questions. For some of them, I shared the answers with the whole class. For others, I had students choose which ones they wanted to research and then report back to the class. I also held a series of mini-lessons on topics that students could sign up for. This was a quick-fix that helped the students gain the knowledge they needed to make the games they had planned. However, it was not the ideal situation.

I was pretty sure there were two reasons for this problem. One, in the student’s minds, there was a disconnect between the assessment and the actual program they were going to write. In many of their minds, they were completing the research plan solely for the grade. They weren’t interested in finding out what they needed to create the program, they just wanted to get a good score. Two, when the students completed Criteria Aii, they hadn’t built any games – so most of them didn’t even know what they needed to find out.

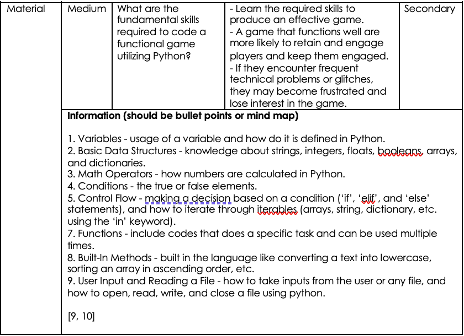

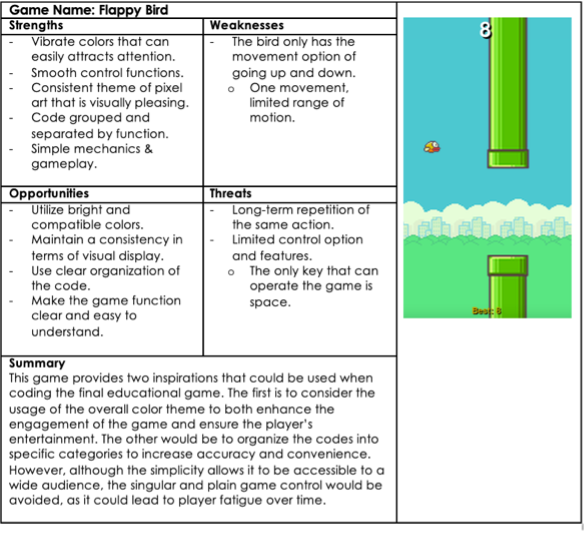

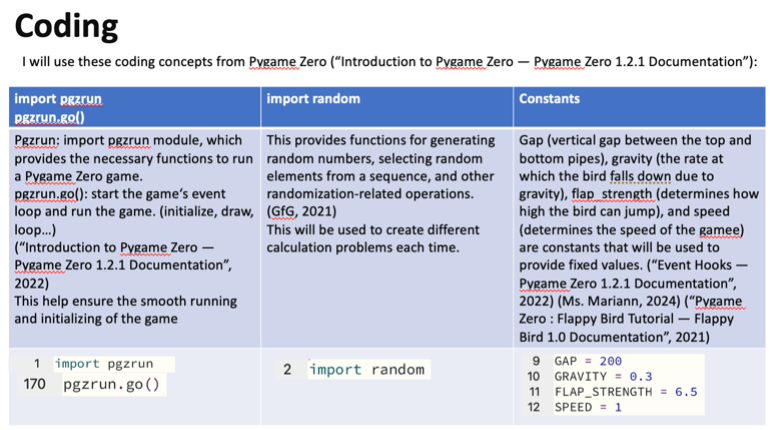

To solve these issues, I changed several things the next time I taught the unit. One of these involved spending 6 weeks having the students learn about how to program in Python. The culminating activity of this part of the unit about getting comfortable with Python was for them to find a game that already existed that they thought would make a good educational game. They needed to add comments to each part of the game and explain what it did. If they didn’t know, they researched to find out the answer. After this, they spent a lesson analyzing a range of educational games they found online and figuring out what made them engaging. Together we made a list of features that most engaging games had. Finally, I asked them to think about what they needed to find out to make the game they had adapted educational as well as engaging as the games they had analyzed. They wrote a range of questions that they still had. These questions were directly related to what they needed to know to create their games and when they did the research related to them, they were interested in finding out the answers.

In addition to restructuring the unit, I also explained the students the issues I had noticed with the way Criteria A is often assessed. Almost all of the students agreed that the criteria for Aii and Aiii are completed by many students to get a good grade – rather than to actually learn what they need to create their product. The students spend a lot of time asking about the format Aii and Aiii are supposed to be in and about details that are more related to getting a good score than to developing a good understanding of what they need to know to make a product.

Semester 1: Criteria Aii Semester 1: Criteria Aiii

Examples of Criteria A work from the first semester

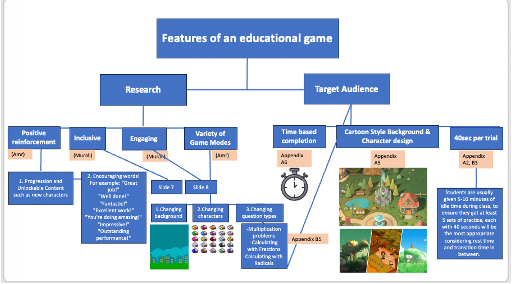

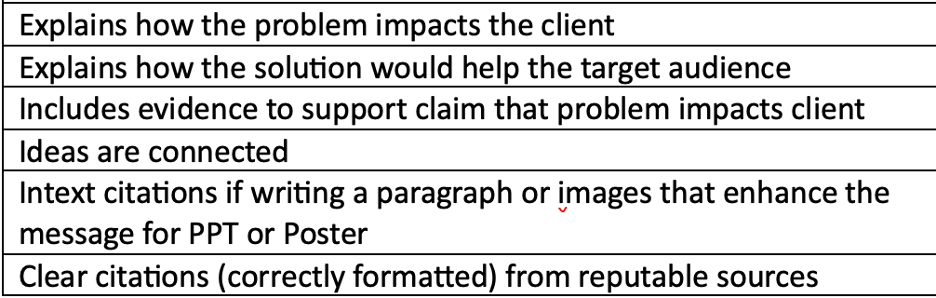

So, in Semester 2, the students and I talked about what an assessment might look like that would give me a clear picture of how well they were able to prioritize research and analyze existing products (criteria Aiii). The goal was to design an assessment that would allow me to successfully analyze their skills related to prioritizing research and analysis of existing products without explicitly creating an assessment for each of these. Together we decided that the students would create an extended design brief that focused on how their research informed what they had determined was necessary to include in their games. They decided that this would take the form of either a PPT or a written brief. I decided on a limit of 1000 words (in negotiation with the students who wanted 3000 words) for the paper or 20 slides (and also a maximum of 1000 words) for the PPT. While there is still room for improvement in defining what this assessment will look like, there was an obvious shift in the students’ work. It was very apparent that they had focused on learning what they needed to find out to make their games.

Semester 2: Criteria A – paragraph option

.

.

Semester 2: Criteria A – PowerPoint option

Many of the changes around the second shift were inspired by a conversation that I had with one of my Grade 9 classes. Before students started working on each of the criterion, we would have a mini-lesson in which we talked about what the expectations for the criteria were. However, when students submitted work it was often a lot more complex and involved than was required for the task. They extended far more effort into completing the task than necessary. This may sound like a positive – students were doing their best work and “going above and beyond”. However, it was an issue because my goal was for students to spend time learning the skills and knowledge needed to create the animations they were working on – not to spend a lot of time completing written work for an assessment grade. While the steps and thinking in the Design Process are vital to this, spending excessive amounts of time in making the documentation their process perfect shouldn’t be.

After the same thing happened on several criteria, I asked the students about why this kept happening. After a bit of discussion, one of the students said, “We often aren’t sure of exactly what teachers are looking for to get a 7, so we do as much as possible so we can make sure we earn a 7.”

Based on the work the students were submitting, this was obviously an issue in my class as well. So, I started the next criterion by coming up with a list of “what a 7 looked like” together. This helped in some ways, but it also resulted in many students superficially checking off the items on the list. For example, “Includes both primary and secondary research” turned into citing exactly 1 primary source and 1 secondary source for some students. The solution to this turned out to be linked to something else I had been working on to increase student agency and provide opportunities for differentiation.

When we talked about each of the criteria, I would explain that they could be met in any form and give a few suggestions such as a video, PPT, poster, or table. I also left it open for students to come up with their ideas. However, every single student continued to choose to write paragraphs. So, I created examples of “what a 7 looked like” in different forms – a PPT with a voice over, a poster and a piece of writing. I then shared these with the students and asked them what they all had in common. This time, the criterion they came up with a broader range of success criteria.

Criteria developed with students in the second round of the lesson.

In addition, before the work was submitted, each student assessed themselves based on the success criteria we had devised together. Then, they each asked for additional feedback from a peer. This time, the work of most of the students was much more in line with what was expected. Many students successfully met the criteria and none of them went so far beyond it that it was obvious they were spending lots of time unnecessarily in the hopes of achieving a better grade.

Over the course of this year, I have tried implementing many of the 12 shifts in my classes. Through this process, I have learned:

- It’s okay if things don’t go as well as expected the first time – just reflect and try again.

- Involve the students as much as possible:

- explain your goal and why it’s important.

- share your ideas for implementing the change

- ask for their ideas (they usually have amazing ones)

- ask for feedback after implementing something new

- It can be more effective to talk to a “focus group” of students first – I have often done this by asking students who are finished with a task before the end of class to form a small group. I then share my ideas and get theirs before starting a discussion with the whole class.

- Make sure to talk to colleagues as well. Many of my colleagues had the same frustrations I did. Sometimes, they had already found a solution I could use. Other times, we were able to talk through possible solutions together. Every time, I came away with some great ideas I could try.

- Many small changes over time can make a significant difference – I was really dissatisfied with many things about the MYP Design Curriculum in the first few months. I still see a lot of room for improvement with the curriculum – and in my facilitation of it. However, through slowly making agentic shifts in my practice, I have found ways to ensure my students have the opportunity to gain the skills and knowledge I think are important for the subject I am teaching.